The year I joined WBBM in 1947 was the same year the station bought tape recorders. The earliest machines could be carried from place to place, but they weighed over twenty pounds. It took some time to see that tape was not like vinyl records. Unlike discs, which simply recorded sound, tape could be edited. I asked an engineer to find a pair of scissors and cut out an unnecessary section of a speech. He joined the next section to the previous one with Scotch tape, which went “pop” in the playback. With experimentation and by cutting the sticky tape on an angle, the pop became almost inaudible.

The year I joined WBBM in 1947 was the same year the station bought tape recorders. The earliest machines could be carried from place to place, but they weighed over twenty pounds. It took some time to see that tape was not like vinyl records. Unlike discs, which simply recorded sound, tape could be edited. I asked an engineer to find a pair of scissors and cut out an unnecessary section of a speech. He joined the next section to the previous one with Scotch tape, which went “pop” in the playback. With experimentation and by cutting the sticky tape on an angle, the pop became almost inaudible.

Whatever the early drawbacks there was one great advantage. The black people being interviewed need not come to the studio in the very white Wrigley Building. An engineer and I could go to the ghettos and get opinions not spoken on Michigan Boulevard.

Once Durham left, WBBM asked me to do a replacement series. No actors, no recreation, just people talking to our correspondent and being recorded on the improved tape recorders. Chicago has always had a race problem, and the late forties were no exception. The program manager was worried.

“Here’s the title, and don’t change it and don’t ask me how to do it.” The title is: The Quiet Answer. Keep things quiet, please.”

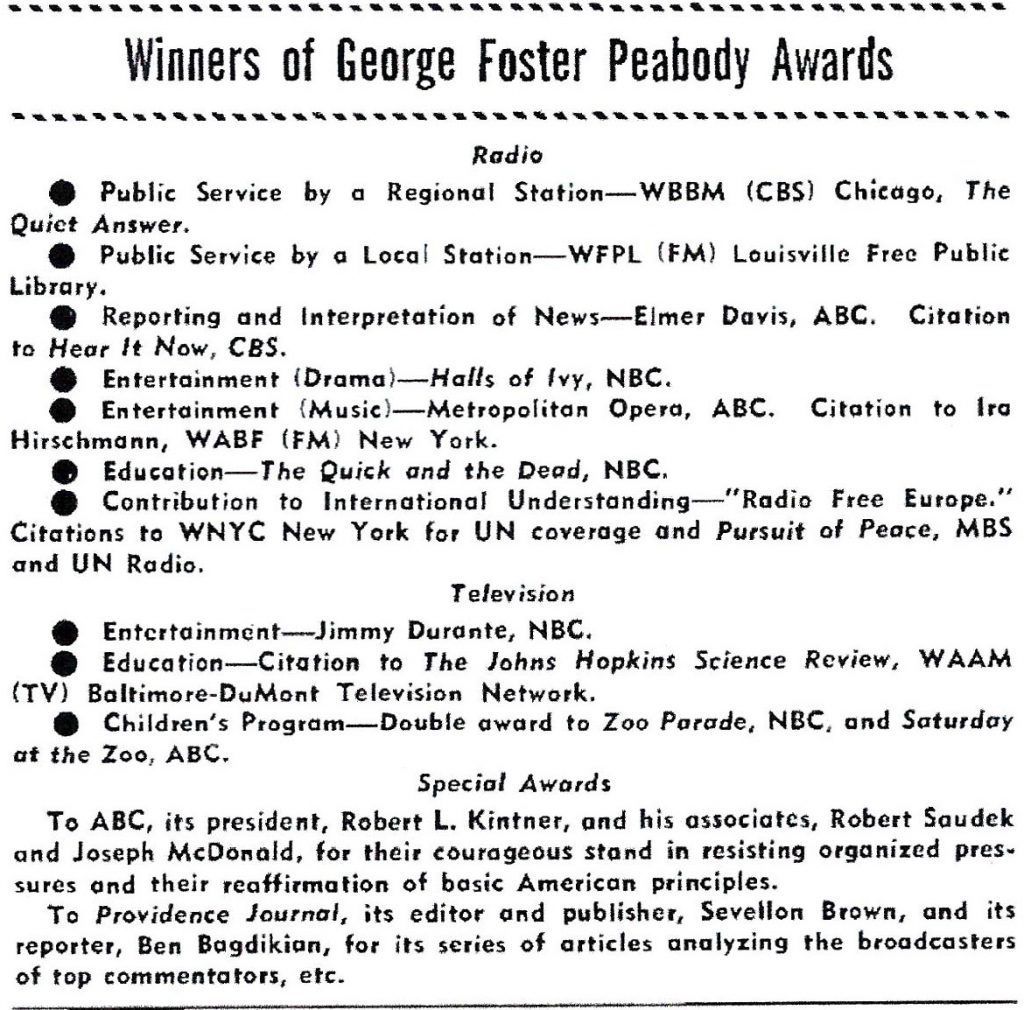

The focus of the series was injustice in real estate. White speculators would buy a house in a white community and sell it to a black family. Neighboring whites would panic and sell out quickly. In turn, middle class blacks would pay more to get out of the dangers in the black ghetto. As a secondary result, police protection in the former white area would diminish by fifty percent. I wrote and produced seven hours in the hot summer of 1947 and won a Peabody, in the days when the Peabody committee gave only seven radio awards and three television awards.

I was proud but WBBM was cheap. The ceremonial lunch and the awards were given in New York, and the Chicago station manager wouldn’t pay my train fare or give me time off.

Technology sometimes leads journalism. The next year an even smaller tape recorder came on the market. I was able to stow it into the trunk of the car and activate it in the driver’s seat. I strapped the microphone under the dashboard. I did a series on narcotics addiction.

“There may be a few crazy whites who use cocaine”, a police captain told me, “but in this town the problem is with the niggers. At worst the whites smoke pod but the real hop heads are blacks.”

Coca Cola originally got its name from cocaine. Cocaine was outlawed because whites in the south thought it drove blacks mad.

One of Professor Lohman’s ex-cons, Broadway Jones, a former bootlegger, lectured on the change in fashionable drugs. In the 20’s Jones had been a bouncer at an opium “den”, frequented by the best people, “including Sophie Tucker.” Opium is best smoked slowly through a pipe. Opium is a heavy wad of dried poppy fluid, stripped from the plant and massaged into a ball. But in a laboratory the wad could be refined down to heroin. The lighter opiate derivative is injected with a light needle and moved quickly for a higher price.

Opiates had been legal until World War I. Dissolved opium was the health drink for many elder and proper ladies. They were called “ladies nighttime elixirs.” Almost every drug store in the country sold laudanum. While still illegal in the 20’s, smoking opium pipes was not considered a major police problem. The elegant and the famous had their favorite addresses in New York. Opium dens were richly furnished. The elegant smoked, and never used a needle. But one day Miss Tucker burst into Broadway’s salon shrieking, “There’s a dope addict here. The bastard has a needle in his arm!”

He was shooting heroin, of course.

Algren viewed marijuana as the opium users viewed their dried poppy leaves–something social, and hardly illegal.

“Some junkies like the ritual of shooting up as much as the drugs”.

He invited me to a shooting session and gave me a small sample.

The first user unscrewed a standard yellow light bulb and replaced it with a red one. He tied his upper arm with elastic until the vein appeared on the surface. The needle went in and the subject pumped the syringe several times. Under the red light, the blood was black. The color pleased him.

“Great stuff,” he told us when he had finished pumping. His companion went through the same ritual.

“Great stuff. It hits right away.”

I had made arrangements with the toxicology lab at the University of Illinois. I sent the sample Nelson had given me to the lab. Two days later I received a call from the scientist.

“Wolff, I hope you didn’t spend too much money on that sample. It’s probably the most expensive after-dinner mint you ever bought.”

Yet I had seen the relief and relaxation on the face of the man who had shot up. He may have been addicted to drugs, but he was certainly addicted to the ceremony.

My good friend, Nelson Algren, a writer best known for his 1947 novel The Man with the Golden Arm, thought drugs ought to be made legal and dispensed through doctors and hospitals—a system tried in Britain. It didn’t work, partially because visits to the doctors, hospitals and pharmacies were too sterile and did not satisfy the need for clandestine ceremonies and rituals…like black blood.

Harry Anslinger, the head of the narcotics bureau of the Department of the Treasury, was infuriated. Algren and his friends were being watched. That’s why I got a call from the narcs.

They came to my office in the Wrigley Building. They made sure I understood that if I were caught with dope I would be busted. They emphasized there‘d be no pass for investigative journalists. I had a few pills in the desk drawer. As soon as the agents had left, I flushed away my possible jail sentence.

Professor Joseph Lohman, soon to be sheriff of Cook County, later treasurer of the State of Illinois, agreed to be my consultant. He asked two of his students, one black and the other white, to help me with my research.

My first set of interviews was at the Joliet Illinois Prison. The convicts jailed on dope and related charges volunteered to be taped. I used only one interview: a handsome woman arrested on a drug related charge.

“Why did you start using drugs?”

“My man was a user. I begged him to stop. I begged him but he wouldn’t.”

“And then?”

“And then—if he wouldn’t come to me, I came to him. I loved him.”

It was very emotional and I believed her. Until, under the table, she shoved her foot gently into my crotch. A sexual SOS.

My black researcher, Jim Howard, suggested I go to the United States Health Service Hospital in Lexington Kentucky. It had a voluntary program for withdrawal. James knew three black users who would go with us. The users each bought a box of Hershey chocolates to give them a sufficient high until they got to the hospital.

The director met me took me to his office and said: “You can’t be a user. You’re overfed. Users are always underfed. They don’t give a damn about food. Tell you what, we’ll say you’re a Red Bird. Red Birds talk fast and slur their speech.”

Red Bird was the street name for Seconal, a red sleeping pill. He knew his drugs. “Methadone—was invented by the Germans in World War II as a pain killer. The second part of methadone is ‘adone’ which comes from their name ‘Adolphine’ from their tribute to Adolph Hitler.”

He added, “Remember, everybody here is voluntary. Even though they walk out on us, at least for two weeks they’re not using needles.”

The government program for opiate detoxification was two gulps of liquid methadone each day. Coupled with counseling, the voluntary patients could expect to be free of their opiate cravings.

Jim and I stayed in our cell for only four days. We weren’t there to kick the habit. We were there to get information and contacts for the broadcasts. Many of the patients weren’t there to kick the habit, either. They too were looking for contacts. They wanted to buy drugs cheaper–“find a New York connection,” one of them said. Lexington was a mall, a continuous convention of The Narcotics Users of the Mid-West.

We brought no microphones. I remember bits of conversation. “H (Heroin) just passes through you and you pee it out. We’re trying to find some way to distill the hospital’s urine. We’re going to refine the sewage system and get the heroin back.”

“He didn’t think methadone would help. So he passed himself off as a cripple, hollowed out his crutch and stashed it with junk. But they took the crutch away.”

“I do the orchestrations here. Billie Holiday just left. It’s sad.”

“What is sad?” I asked.

“I had to rewrite the orchestrations for the next chick. Up a third.”

Howard picked up a fair share of contacts on the south side of Chicago. He was given no names, but locations where drugs were traded. We staked out the sites. I gave some addresses on the air.

One was a corner on 43rd street next to a bar.

It cost me my job.

The brother of the head of WBBM owned the bar. The police were embarrassed. When I named the bar on West 43rd, police simply had to close it, even though they had taken the proper payoffs from the owner. Brother complained to brother. The head of the station then talked to the sales manager. I was invited to have a drink at the Wrigley Building bar where the WBBM sales manager reluctantly fired me. I had put the brothers in an awkward position. The cops had spared the correspondent, Fahey Flynn, “because he just read the copy, and anyway he was an on-the-air personality.”

Embarrassingly for everybody at WBBM, the series, Report Uncensored, won a Peabody award in 1950. Once more, someone else received it in New York. You can hear this radio series here. (You’ll have to scroll down to click to download the MP3 to your computer.)

Images

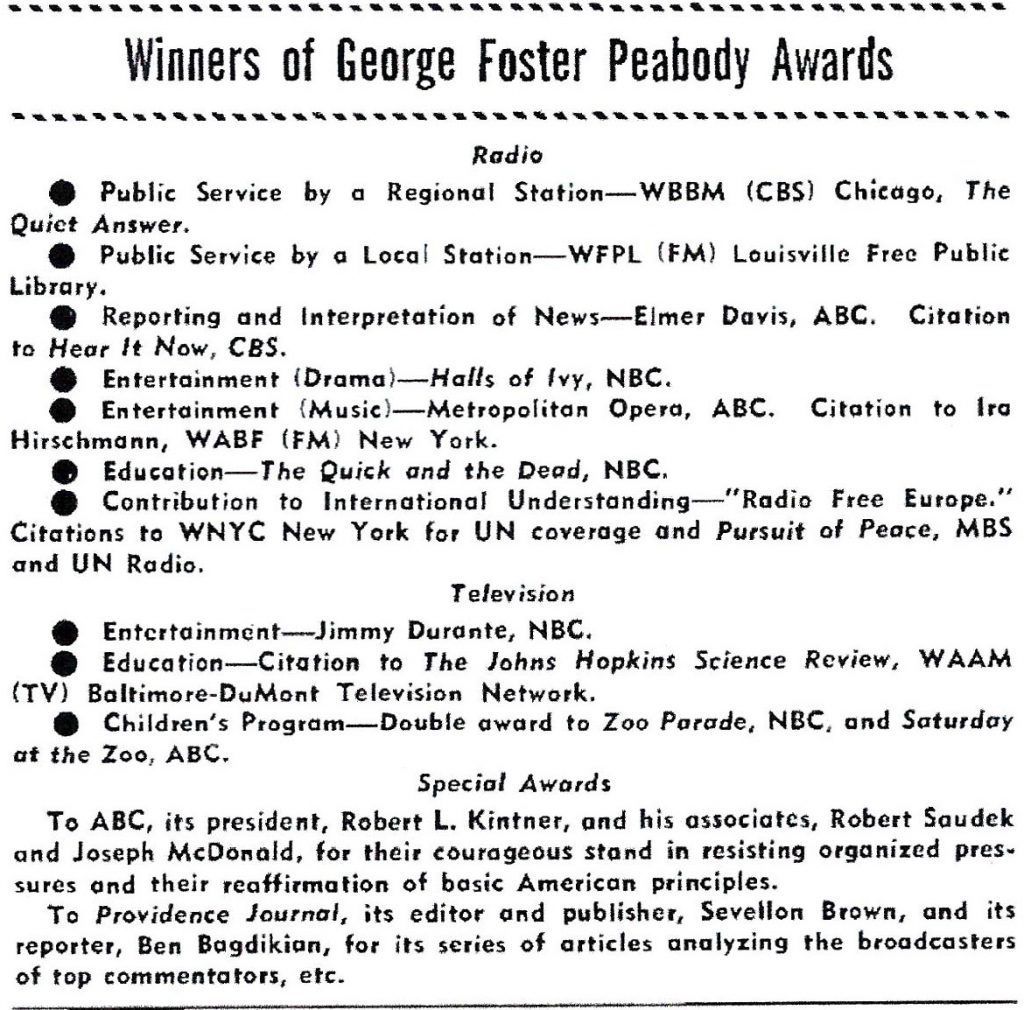

Perry Wolff, “Broadcasting Telecasting,” April 30, 1951, page 26

Peabody Awards, “Broadcasting Telecasting,” April 30, 1951, page 26

References

Old Time Radio Downloads, Juvenile Delinquency in Chicago.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

The year I joined WBBM in 1947 was the same year the station bought tape recorders. The earliest machines could be carried from place to place, but they weighed over twenty pounds. It took some time to see that tape was not like vinyl records. Unlike discs, which simply recorded sound, tape could be edited. I asked an engineer to find a pair of scissors and cut out an unnecessary section of a speech. He joined the next section to the previous one with Scotch tape, which went “pop” in the playback. With experimentation and by cutting the sticky tape on an angle, the pop became almost inaudible.

The year I joined WBBM in 1947 was the same year the station bought tape recorders. The earliest machines could be carried from place to place, but they weighed over twenty pounds. It took some time to see that tape was not like vinyl records. Unlike discs, which simply recorded sound, tape could be edited. I asked an engineer to find a pair of scissors and cut out an unnecessary section of a speech. He joined the next section to the previous one with Scotch tape, which went “pop” in the playback. With experimentation and by cutting the sticky tape on an angle, the pop became almost inaudible.