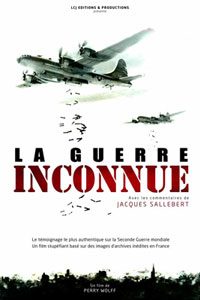

The Belgian proj ect helped finance two feature-length documentaries made from Airpower: La Guerre Inconnue (the Unknown War), and Kamikaze. I bought the footage from CBS and cleared the rights. To distribute in France I needed a co-producer who recommended technical facilities and personnel.

ect helped finance two feature-length documentaries made from Airpower: La Guerre Inconnue (the Unknown War), and Kamikaze. I bought the footage from CBS and cleared the rights. To distribute in France I needed a co-producer who recommended technical facilities and personnel.

The editor was Jeanne Gilot, a woman in her thirties who was technically capable and physically strong. She was attractive, a brunette with small solid breasts that I had to disregard. We sat close together for hours at the editing machine. Though we were shoulder to shoulder, our body language was proper.

An early feminist, during working hours she would not permit me to carry heavy film cans from the shelves to the editing machines. “Perry, c’est mon travail. Je ne suis pas un fleur bleu.” I am not a shrinking violet is how I translated it, but my French was never too good. She glared and I retreated.

At quitting time she went to the ladies’ room and returned with lipstick properly placed and a bit of eyeliner that set off her best feature, her blue eyes. She stood next to the coat rack. I was then allowed to take her garment from the rack and help her into it. She moved from female to gentlewoman, and I went from patron to gentleman.

We always used the vous form; never the tu. From the formal to the familiar was a great leap for the French.

While watching her edit I noticed she wore a wristwatch—an expensive Boucheron with the fine gold mesh strap. I was quizzical.

“This came from my married lover,” she said.

One day her wrist was bare. She said nothing, but I thought I heard her cry. I never questioned her, and I never learned more. I was as disappointed as you may be, dear reader.

As the weeks went on she became used to my terse style both in editing and writing. “You are very good Perry. I am learning a lot about America.”

When the rough cut was finished she sat beside me in the sound mixing room. Events became heated. The sound mixer was excellent…in the morning. His equipment was obsolescent even for the late ‘50’s in France, but he handled it well—until lunch. We ate at a small café on the Avenue du Boulogne where a steak, salad and a half bottle of red wine cost about a dollar. He would drink his wine, and sometimes mine. When we went back into the sound studio he was half the professional he had been at noon. Error after error, retake after retake. I was paying for his services and the facilities. I called his attention to his inept work and blamed the wine.

“Monsieur, vous êtes un puritain. Le vin rouge au déjeuner est une tradition ouvrière protégée par les syndicats.” (Red wine at lunch is a worker’s tradition protected by union rules.)

Then he added something derogatory using the tu in French, which I did not understand, but Jeanne did. She was startled. I could not understand her French, but I understood her tone to him and his sullen retort to her. Insult to insult. He quit two days later. Jeanne finished the mix, but would not take screen credit except as the editor.

When she and I said goodbye, it was not with the French triple kiss—cheek, cheek—cheek, with pelvises decently apart. It was a long hug, faces over the shoulder, and body warmth to body warmth. It said far more than sex ever could. The heart and the head are many inches above the gonads, and that much closer to heaven.

“Tu vas me manquer,” she said at our last meeting. Tu, she said. Not vous. She would miss me.

Distribution in France

La Guerre Inconnue (The Unknown War) was a recapitulation of the air war in Europe. Kamikaze discussed the defeat of Japan. Kamikaze was received well in the major French newspapers. While the audience for documentary features is always small, the film turned a profit.

The co-producer never bothered to see La Guerre Inconnue. He was well connected with the French government. He arranged to have the opening at the grand Palais de Chaillot with dignitaries and veterans of foreign war present. Every seat was taken.

At that time the belief of the French military was that one of their armored division had liberated Paris. They had entered Paris without firing a shot. But the American 4th Division had prepared the way for them. The GIs took the casualties but the French took the credit. General LeClerc’s troops were shown leading the liberation of Paris.

I did not say it directly—indeed he film only hinted at it—but that was too much. Indignation led to rejection. Several of the anciens combatants rose to their feet and left in the middle of the movie.

My co-producer apologized profusely—even to the officials who had made the arrangements. A few days later he gave me some bad news. The French government imposed a tax on all movie tickets. For deserving films, this aid to the cinema was returned to the producer. Since technically, since the film had a French visa, this money went to him, and the American producer would have to wait. He was planning another movie, and he would invest my share in it.

The money could not be transferred out of France. In the meantime he had invested in a successful comedy, La Belle Americaine, and made a fortune with it. Unfortunately the fortune was reinvested in a remake of The Three Musketeers, which flopped.